Basic Facts About Oestrogen, Progesterone & Androgens

What is Oestrogen?

Every month after menstruation, the body begins to rebuild oestrogen levels in the form of oestradiol (the active form of oestrogen). Some oestradiol is converted to a weaker form called oestrone. Oestradiol and oestrone are then secreted into the bloodstream and travel to oestrogen-sensitive cells to stimulate cell growth. Peak oestrogen levels are reached just prior to ovulation and then fall just before menstruation begins.

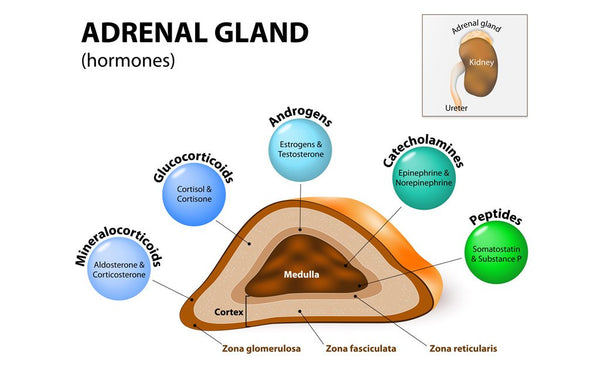

Oestrogens are made from progesterone and/or androgens in the ovarian cells. After menopause, oestrogens are converted from the adrenal-producing androgens found primarily in body fat. Oestrogen and progesterone are both antagonistic and yet sensitive receptors for the other. Progesterone has a balancing effect on excessive oestrogen.

Sources of oestrogen:

- ovaries, adrenals and adipose tissue

- enterohepatic production (aromatisation of androgens to oestrone)

- exogenous (xenoestrogens from the environment)

Oestrogen is a hormone produced in the ovaries and signalled by the pituitary gland. It exhibits sustaining effects on the female reproductive system. Being the dominant female hormone, the functions of oestrogen are:

- supports secondary sexual characteristics

- blood cholesterol regulation

- moderate levels modulate GnRH

- promotes the growth of reproductive tissues, bone and cartilage, epithelial linings (uterus, fallopian tubes and vagina)

- increases cervical mucus (clear)

- vasodilation

- antiatherosclerotic

- determines feminine body proportion

- increases protein anabolism (synergistic with growth hormone)

- promotes more fluid sebaceous secretion (anti-acne)

- increases fluid retention

- endometrial proliferation

- regulates acidity in the vagina

- controls fluid and electrolyte balance

- stimulates mucous secretion

Understanding oestrogen dominance

Many female health problems and symptoms arise due to hormone imbalance – typically oestrogen dominance. Oestrogen dominance or progesterone deficiency occurs in a woman where there is a high oestrogen-to-progesterone ratio. Symptoms of this hormonal imbalance include:

- tender and fibrocystic breasts

- a tendency for increased body fat

- increased blood pressure

- thyroid hormone imbalances

- decreased sex drive

- decreased blood sugar control

- zinc depletion and copper retention

- increased risk of endometrial, breast, and ovarian cancers

- impaired liver and gall bladder function

- increases incidence and growth of fibroids

- hair loss and facial hair

- impaired immunity

- migraines

- miscarriages

- pre-menstrual symptoms, PCOS, endometriosis, fibroids and PMDD

- increased blood clotting

The table below demonstrates the effects of varying oestrogen levels:

|

LOW OESTROGEN |

HIGH OESTROGEN |

|

Follicular phase of cycle |

Luteal phase of cycle |

|

Long cycle |

Short cycle |

|

Scanty flow |

Heavy bleeding |

|

Missed cycles (amenorrhea) |

Dysmenorrhoea |

|

Reduced ovulation |

Reduced progesterone |

|

Later menarche |

Early menarche |

|

PMS, endometriosis, cyclic breast disorders, fibroids, menopause symptoms, risk of estrogen-dependent cancers |

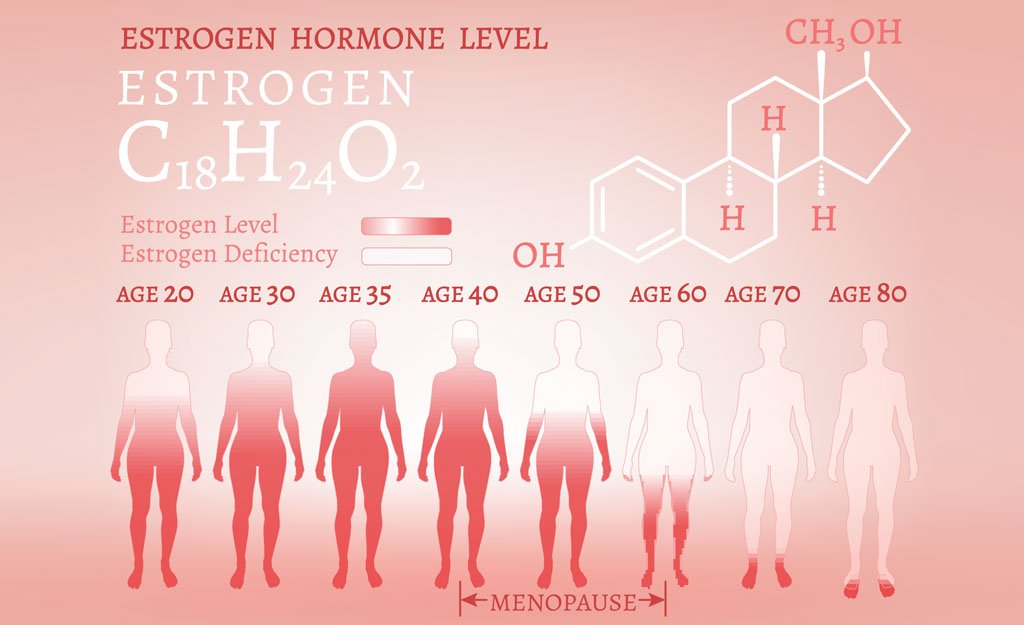

Oestrogen has positive effects on the cardiovascular system, reproductive organs, bones, brain, and skin. Issues experienced during menopause such as memory loss, osteoporosis and vaginal dryness simply validate the importance of maintaining optimal oestrogen levels. However, having too much oestrogen in the body may increase the risk of hormone-related cancers such as endometrial, prostate and breast cancer.

The final piece of the puzzle is the reduction in oestrogen levels leading to menopause. The ovaries reduce their production of oestrogen, triggering the elevation of FSH and LH. This, in turn, triggers the characteristic symptoms of menopause. The ovaries and adrenal glands continue to produce some oestrogen; however, if the drop is considerable and the adrenals cannot cope then the symptoms of menopause can be dramatic until the body balances itself.

Low endogenous oestrogen levels are associated with the following conditions:

- Menopause – immediately before and following the firm cessation of menstruation, women experience a rapid loss of bone density (demineralisation). It may then plateau after the initial five years and decrease at a rate of 1% annually.

- Hypothalamic amenorrhea –may also be seen after cessation of the OCP and can be brought about by other reasons (excess dieting, anorexia, rigorous exercise, fat loss).

- Premature menopause – a rare condition in which women experience menopause before the age of 40. A decline in the production of oestrogen within the ovaries may account to premature bone loss.

- Premature ovarian failure

- Hypothyroidism – low thyroid function may be associated with low bone density if left untreated.

The second source of oestrogen is derived from the conversion of androgens to oestrone by the aromatase enzyme. This process is called aromatisation and occurs predominantly in the muscles and fatty tissue (adipose).

Women in the postmenopause phase will derive most of their oestrogen through this aromatisation of androgens. Often, this conversion of oestrogen is enough to sustain them; however, if the adrenals are in poor condition due to a lifetime of stress, nutritional deficiencies, and other negative factors, the conversion is decreased and the symptoms of menopause are more extreme.

What is Progesterone?

Progesterone is one of two main hormones made by the ovaries of menstruating women (the other being oestrogen). These two hormones are antagonistic yet sensitised receptors for the other. Progesterone has a balancing effect on excessive oestrogen. Progesterone, which is also made in smaller amounts by the adrenal glands, is the precursor to oestrogen, testosterone and the cortical steroids.

Progesterone is made from cholesterol and is synthesized from the steroid pregnenolone, which itself is derived from cholesterol. It is a hormone that depends on ovulation and the development of the corpus luteum (luteal phase of the cycle) for its production. Due to ovulation rates declining during the perimenopausal years, the amount of progesterone present also begins to diminish. In those cycles where ovulation fails completely, progesterone levels are negligible.

Specific functions associated with progesterone

- a precursor to other sex hormones, including oestrogen

- maintains secretory endometrium (uterine lining)

- necessary for the survival of the embryo and foetus throughout gestation

- protects against fibrocystic breasts

- natural diuretic

- helps use fat for energy production and normalises blood sugar levels

- natural antidepressant

- helps thyroid action

- restores sex drive and benefits libido

- protects against breast and endometrial cancer

- builds bone and is protective against osteoporosis

- is a precursor of cortisone synthesis by the adrenal cortex

- induces cervical mucus to become thick (sticky)

- inhibits prolactin

- promotes survival and development of the embryo and foetus

- acts as a precursor to other steroid hormones (oestrogen, testosterone, cortisol)

- normalises zinc and copper levels

When a woman’s cycle is functioning correctly, oestrogen is the dominant hormone during the first two weeks of the menstrual cycle. In response to ovulation, progesterone then assumes dominance for the final two weeks of the month. When the pituitary gland sends a message to the ovaries to stop producing progesterone, the menstrual cycle begins within 48 hours.

Due to ovulatory cycles, progesterone levels typically decline before menopause starts. This is followed by a decline in oestrogen. Progesterone tends to fall to almost zero while oestrogen declines to about 40-50%. This situation leads to an imbalance between oestrogen and progesterone causing an increase in oestrogen activity which is commonly described as oestrogen dominance.

Progesterone production is reliant on ovulation (luteal phase of the cycle) and the development of the corpus luteum. With the decline in ovulation when a woman moves from her fertile to non-fertile years, the biological changes that take place with oestrogen also occur with progesterone.

Progesterone is commonly called the 'pregnancy hormone' as it is produced in larger amounts once conception takes place. Its primary role in pregnancy is to convert the endometrium to its secretory stage to prepare the uterus for implantation.

What are Androgens?

Androgens are often mistakenly thought of as a “male only” sex hormone. However, androgens are also natural to the female body, where they are produced in the ovaries, adrenal glands and other tissues. Androgens are necessary for estrogen synthesis in adult women and have been shown to play a key role in the prevention of bone loss. They are also necessary to maintain or boost sexual desire and satisfaction.

At menopause, the average reduction in androgen production by the adrenal glands is 50%. Maintaining ovarian and adrenal androgen production is an important focus for menopausal support. Supporting adrenal gland function throughout the menopausal years is fundamental to hormone control as they produce androgens that serve important functions. Postmenopausal women rely on the adrenals to produce androgens after a decline in oestrogen production by the ovaries. Androgens are converted into oestrone and used in the synthesis of oestrogen.

Another hormone influenced by menopause is testosterone. Testosterone is an androgen hormone produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands. Testosterone levels also begin to decline as a woman transitions into menopause. Women actually need small amounts of testosterone as part of the mix of hormones that keep the mood, energy levels, sex drive, and bodily functions working smoothly. Without the sustaining and maintaining effects of testosterone, they are left feeling depleted and lacking vitality.

Common symptoms of decreased testosterone levels:

- reduced sex drive or sexual response

- lack of energy and motivation

- a diminished sense of well-being

- depression

- poor memory and concentration

- a decrease in muscle mass

Why androgen production is equally important during menopause

- Maintain sex drive. Women normally experience a dip in their sex drive after menopause. Decreased libido could be the result of lower testosterone levels in the ovaries. Well-functioning adrenals help sustain the production of testosterone to maintain libido.

- Preserve bone health. The correct balance of testosterone supports the growth and strength of healthy bones to maintain bone integrity and prevent osteoporosis.

- Reduce pain levels. Androgens improve pain responses and aid with pain management.

- Protect cognitive health. Changes in cognition and cognitive fatigue may be related to fluctuating hormone levels.

- Sustain lean muscle mass. Androgens are anabolic and help promote muscle tissue growth. Poor androgen activity has also been linked to faster ageing.